I wanted to tell our story with a greater scope than the usual small slice you’d see of a hyper-specific time and place. I wanted to share the objective history and take the audience on a ride through the unfolding of our particular subculture’s roots, and I wanted to do so visually.

– Victor Friedman

Words by: Victor Friedman

Andy Strahan, soyale. Picture by: Javan Makhmali

Andy Strahan, soyale. Picture by: Javan Makhmali

I knew Vic had been working on this obsessively for years, and I expected a lot, but it far exceeded my expectations. I told him it probably has the most replay value of anything I’ve seen in the last decade.

– Tom Smith

ELF banner.

ELF banner.

The way I conceive of the early years, every six months or so was like a different period (complete with new styles, a slew of new tricks, etc.). Everything evolved so rapidly. Go back and watch VG2 back-to-back with VG3. I remember when VG3 came out, our reaction was: “Everything’s different now,” and then we echoed that sentiment later the same year with Fast Shoes and again the following year with Plastic Balance. I guess, technically, every six months could be considered an era unto itself, but there were enough commonalities that it just seemed to make more sense to me to consider those “periods” within an overarching era, which I suppose ended in late 2000 with balanced fastslides (which, incidentally, Drew Bachrach was doing in 1996, if not earlier) and freestyle (ungrabbed) tricks. Because the montages are mixed-year, it’s very useful to be able to date tricks based on hardware, clothing, etc., for those sections. A number of tricks in this project were highly innovative, so it adds an extra layer of appreciation to be able to identify the different periods within the era, and also to know which tricks came out when. If you have the greater context for each period, then you can compare apples to apples – you can look at a trick, see that it was early ’96 and think about how it stacks up to VG3, then see another trick that was mid-’96 and see how it stacks up to VG4. It’s obviously easier with the non-montage sections, which are explicitly labeled, so you can look at an Era profile from 1995 and put it in the context of The Bottom Line or Hoax II and look at another one from 1998 and put it into the context of FOR or Elements. If you know that someone was doing something before it was officially “invented,” that’s obviously very meaningful, and it’s just one of those things that will either be extremely obvious to you or it won’t. It just depends on the individual viewer’s personal knowledge of skating history.

Despite all of the mixed-year montages, there is an overall chronological narrative build to the movie (largely due to the profiles) so, in order to get the full effect, I’d definitely watch it in one sitting (it’s the same length as Hoax II).

Capturing history perfectly – so that people feel like they were there, and you know that you’ve done justice to the beauty of the experience – is just impossible (we skated almost every day, and most of the time there were no cameras rolling). How do you squeeze nearly a decade into an hour and a half? In an ideal world, this movie would have been an hour longer because I could have made dozens more profiles (no exaggeration), but that just wasn’t feasible. Nevertheless, I’m convinced that this is as good as this project could have possibly been. The only way it could have been better is if we had known that we were filming for it back then so that we could have captured a lot more of our skating. I put more than three and a half years into this; people will never know most of what I did for this project. I spent more than a year just on the final polish. Era speaks for itself. I originally wrote a 20-page addendum to create further context for what you are about to watch. I ultimately scrapped that addendum because it became extraneous. The movie does what it’s intended to do, and it does a damn good job of it.

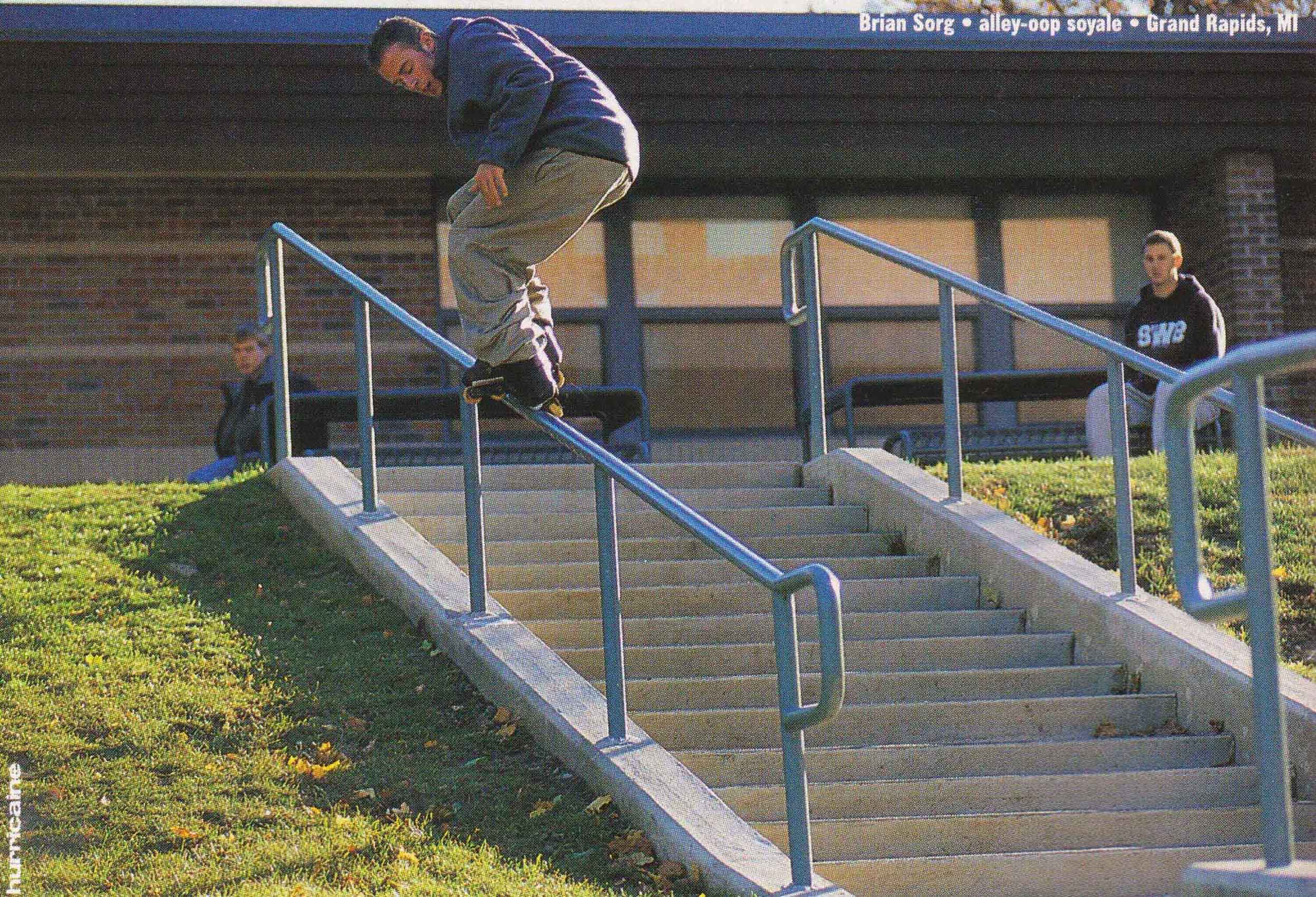

Sean Steingold, royale. Picture by: Marni Bright

Sean Steingold, royale. Picture by: Marni Bright

I hope people get something out of this project. I’m honored to bring light to a community that was forever in the shadows.

Thanks for checking it out.

And thanks to Tom Smith and the Blade Museum for their continued interest in – and support for – the roots of Michigan rollerblading.

All the best,

Victor Friedman

Victor Friedman, backslide. Picture by: Jordan Friedman

Victor Friedman, backslide. Picture by: Jordan Friedman

P.S. Make sure to check out the original In Code (the ELF team video), Mad Lads, and the Era leftovers below.

ELF team video

Thanks to Drew Bachrach for the use of the original ELF “In Code.”

Mad Lads

Thanks to Mark Thomas for the use of “Mad Lads.”